On Unsteady Heights: The Life of Edith Bedal

Editor’s note: The following is a chapter from an upcoming historical fiction book by Richard Porter.

1.

The horses stumble on the muddy slope, their hooves leaving gashes in the soil. Below them gapes a ravine filling with the runoff from rain that falls in black curtains onto the side of Mount Pugh. Wind rushes up from below — a blowing, freezing spittle, so that it seems like the wet is coming from all directions at once.

The girl dismounts and checks on the horses. She lashes oil-coated tarpaulins over the 200-pound packs, pulls the rope tight and deftly ties a half-hitch knot. The horses are spooked now, so she leads them on foot, two bridles in her hand, squinting through the dusk to see the root-rippled trail before her and step cautiously onto slick rocks and patches of heather. She makes her way skyward into the deep indigo evening.

She knows that pack horsing up and down the slopes of the Cascades isn’t nearly romantic an endeavor as folks in town or city folk assume. Rain falls in rivulets from her oil-coated hat. Her oiled boots have started to leak as she steps through springs of water forming mountainside cascades.

She whispers as she climbs: I am the resurrection, and the life: he that believes in me, though he were dead, yet shall he live…

Then, rounding a boulder, she sees a telltale flash of a lantern on the ridge above. She reaches the fire lookout and tethers the horses. The rain is coming from above, from below, from in front. Quickly, she helps the lookout attendant unload the supply boxes filled with coffee, flour, butter, and milk. They stack the boxes in the lookout. Exchange pleasantries.

She knows the way down will be slick, but the unburdened horses will be sure-footed. She carries a lantern. As long as the lantern shines on the next interval of path she can walk out off this mountain and get to the enveloping embrace of the home-fire.

2.

I am the resurrection and the life… she stands in the congregation to recite the verse. She attends the Methodist church in Darrington. She once went to a bake sale at the Baptist church up in the Sauk River Prairie, but her mother warned her away from the string music and sing-song prayers of the “tar heel church.”

She and her sister have ridden from their homestead seventeen miles this morning to be here at church. She stands up and speaks amid the pews filled with her peers. She speaks the twenty-fifth and twenty-sixth verses of the eleventh chapter of the Gospel According to Saint John.

Lazarus. Come forth, Lazarus. Though he were dead, yet shall he live.

The girl and her sister are incongruous amid the congregation: two caramel-skinned ladies in a sea of blue-eyed Scandinavian faces. Their mother is the daughter of the chief of the Sauk tribe of Indians. Their mother weaves baskets and teaches the girls where to find the blueberries in the mountain valleys and along the edges of alpine lakes. Their father is a man from Indiana who homesteads up the river and cuts cedar bolts.

The family homestead is a cabin at the very base of Sloan Peak. On a clear night the sky mists over, hazy with Milky Way stars, and on these clear nights the mountain blocks out negative space: a bulky conical void thrust into the ether, like a tusk from below.

Theirs is a remote, isolated life. A bolt cutter once gifted Edith a pulpy citrus fruit. She had never seen an orange before. She cradled it gently, almost afraid to harm this exotic, edible globe. “I thought it was the most beautiful and fragrant fruit I’ve ever seen,” she later wrote. Seventy years on and she never forgot about the aromatic Valencia.

She was well-spoken, grammatically precise and enunciated. The girl’s elocuted grammar was forged in the fiery passages of the King James Bible and honed in a one-room schoolhouse outfitted with a four-legged iron stove. Folks in town weren’t sure what to make of these sisters who were both white and non-white.

Their homestead was so set apart, so remote, that the area itself became synonymous with their surname: Bedal.

3.

But the thing about being alone? It’s also incredible. The sisters strap woven baskets on their shoulders and travel up the slopes of Sloan Peak. It’s springtime and the pastures and alpine lakes brim with trillium, heather, and foxglove. The sisters fill their baskets with blueberries, and nap on a rock overlooking a lake, feeling the first substantial sunshine of the year as it strengthens them to their marrow.

Yes, the mountain hurls squalls at pack animals, weeps in landslides, looms ominously in the lonesome night. But, meekly, it also opens its hands to offer endless vernal recreation: the simplest of joys in breathing cool air. To climb and explore and eat your fill straight from the berry bush.

This is the way she learns the mountains and valleys; just as a sailor knows his sloop, a tailor his twine, a Cooper his barrow. She is the go-to local horse packer, solely qualified to navigate the Sauk and Stillaguamish River Valleys and the peaks therein, delivering supplies to fire lookouts, hauling away scrap iron, moving shingles. These jobs pay cash and it’s the Great Depression. Some days it is glamorous and unthinkably, stupidly beautiful. Some days it’s a nighttime slog downhill in the dark with a prayer that your boots and pack horses stay steady upon the rock.

4.

Decades later, she lives in an apartment on First Hill in Seattle. She works as a waitress and makes pretty good money in tips. She has saved up and she bought herself a television. She’s taking driving lessons.

One day, while practicing lane changes with her driving instructor on Capitol Hill she glimpses the Cascade Mountains to the east. They seem to be glowing in the evening light.

In an instant she knows. Maybe she didn’t know she was lost until she wasn’t lost anymore.

She writes later, “I’m thankful that I live in the age of the automobile.” For she packs that very month and, with her newly honed driving skills she travels north and east, driving her own car. There is no more Bedal. The homestead is gone, wrecked to rubble by landslides.

She pulls into town in Darrington. Gets out of her car.

Above her stand no high rise buildings. Instead, in the sky towers Whitehorse Mountain, adorned in a fresh bridal dress of white snow. Pristine. Crystalline. Waiting.

The above post is a chapter from an upcoming historical fiction book by Richard Porter.

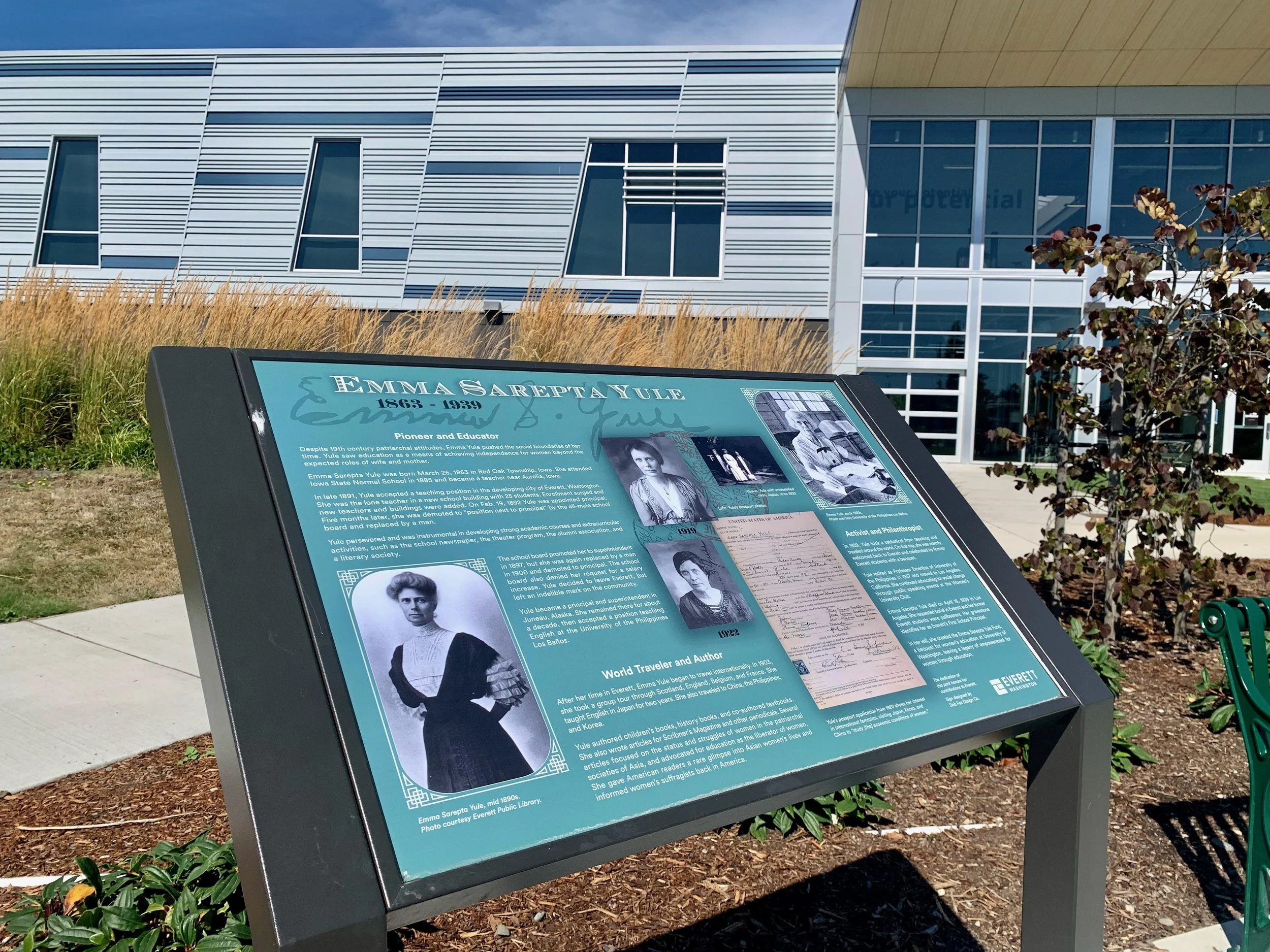

If you’d like to order his first book about Everett history, please click here.

All photos and information for this article come from “Two Voices” the excellent autobiography of the Bedal sisters. Thanks to the Northwest History Room for research assistance.

Richard Porter is a writer for Live in Everett.