A Return to the Sea

Editor’s Note: Originally published September 15, 2017.

The sea is with us.

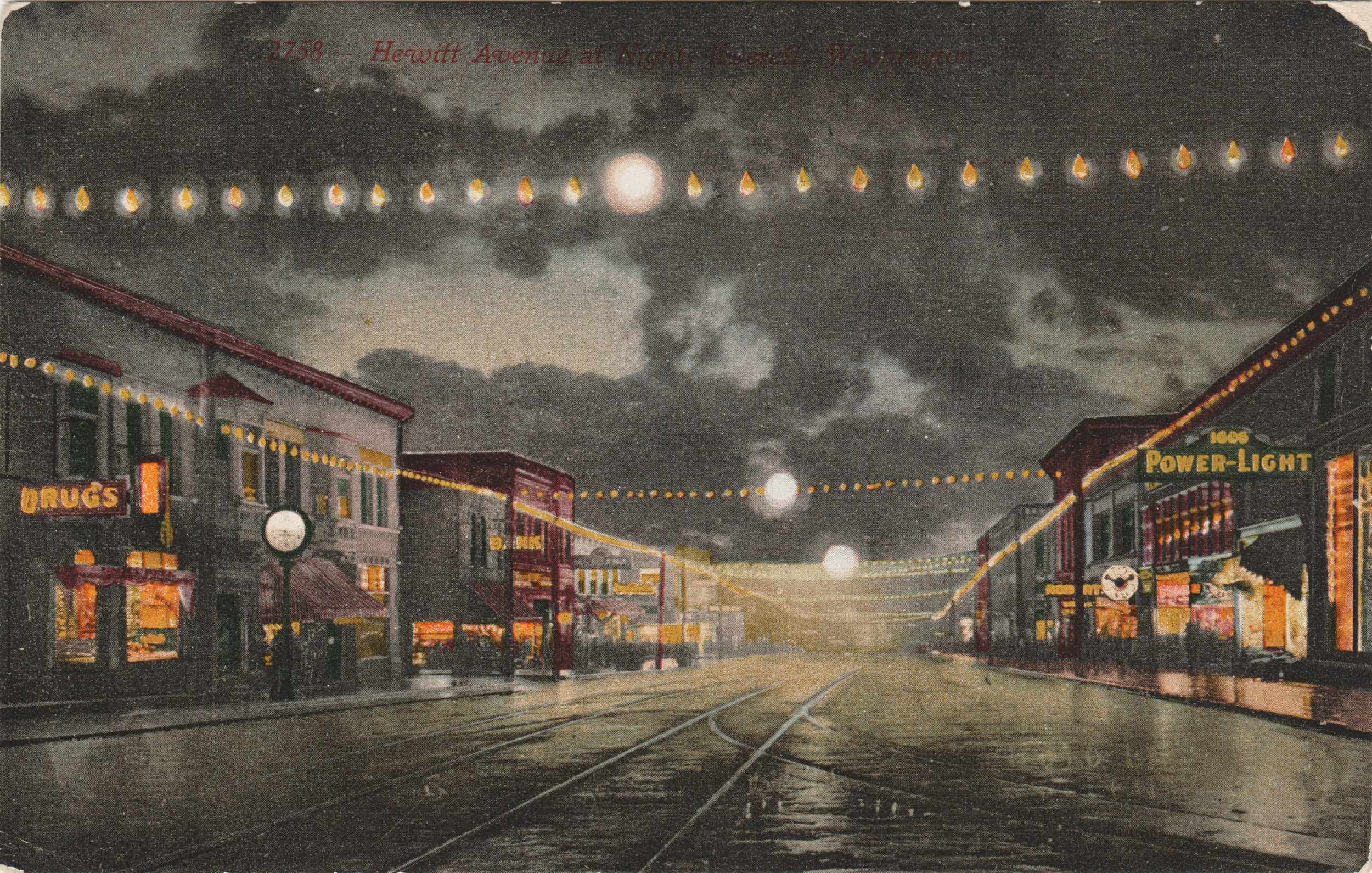

It’s part of our nomenclature. Scuttlebutt, The Anchor, The Soundview, Seas the Day Cafe, The Cannery (RIP), Fisherman’s Village Music Festival.

If our names are our identity it seems we can’t shake our maritime history.

The Puget Sound was our whole reason to be here in the first place. The mills needed a place to float log booms and a port from which to ship shingles. The waterfront sprouted canneries, dry docks and maritime supply stores.

So I’ve begun researching maritime history and lore. It’s what I do for fun these days.

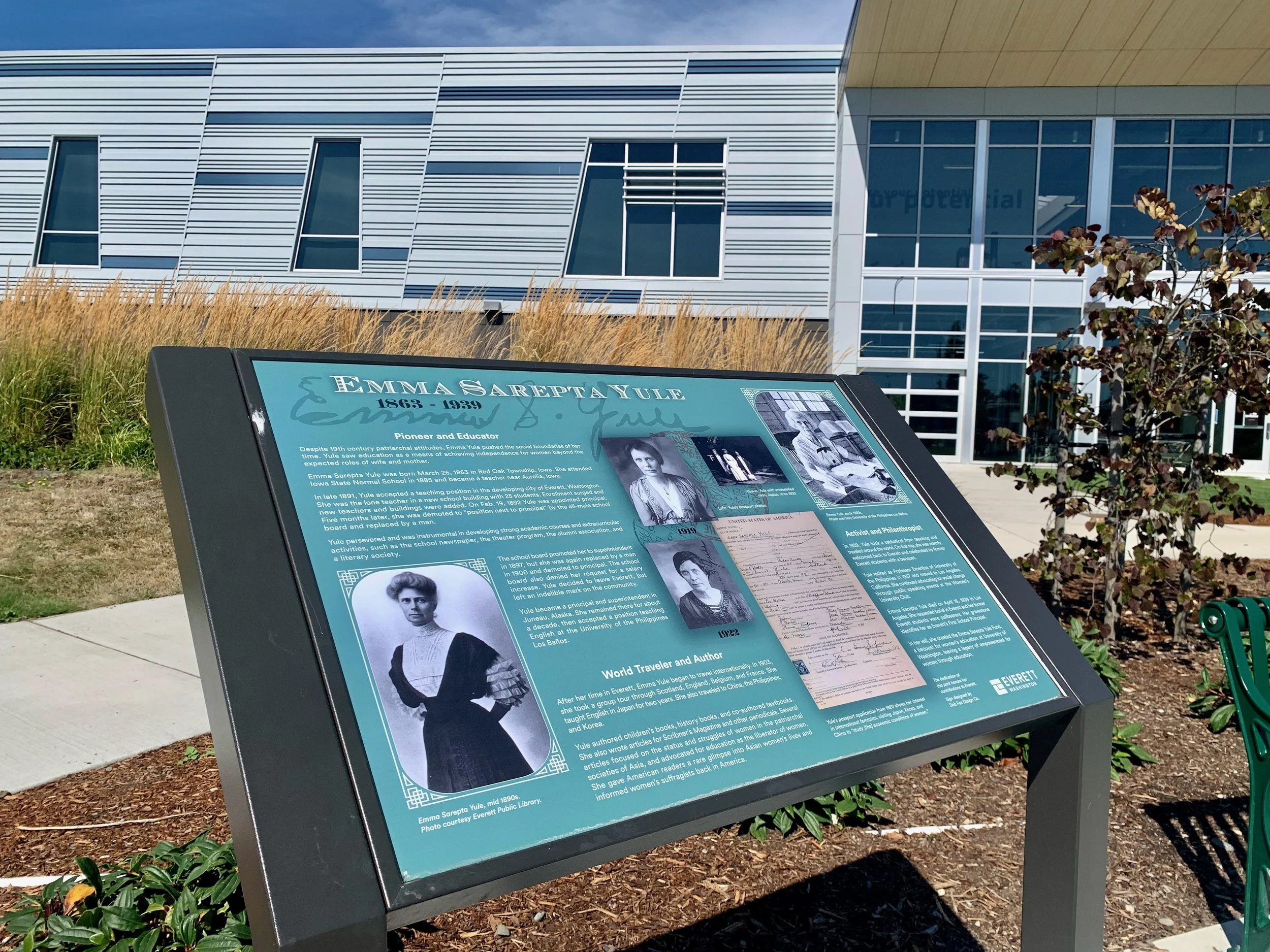

This week I was working with local historian Dave Ramstad in the Northwest Room at the library. In the course of our research I stumbled upon a fact that took my interest to another level.

My home, built 1942, was originally constructed as part of a housing project for dockworkers. The Polk city directory for that year lists the original inhabitants of my home as Thomas and Alfretta Hanson. Their occupations are both listed as “fisherman.”

So there it is: the history of the waterfront, manifest in a place where I live and move and have my being. A place where I make sandwiches and watch Roseanne reruns.

The story of the sea is one of romance.

There are boathouses, buoys, sailor’s caps, hand-rolled cigarettes, colorful profanity. And, yes, there’s that great grey waterway, the beautiful Puget Sound.

In the mid-20th century, the waterfront was our common ground. Dock workers, millers, shingle weavers, fishermen, stevedores and longshoremen walked there from residential North Everett.

There used to be a set of stairs leading from the bluff at Grand Avenue Park to the waterfront. These were called the "workers' stairs."

In days of yore (and not even that far yore) anyone could rent a dinghy or a skiff from a public boathouse and spend the day crabbing. Fishing derbies were a common community event with prizes awarded for the biggest catch.

There seems to be a sense of conviviality that pervaded even the most grudging of maritime tasks.

Consider “slimehouses.”

Slimehouses were fish canning and processing plants on the waterfront. Women stood at long counters, calf-deep in water. They gutted and cleaned salmon, packed them into cans. The teen girls employed there wore silk dresses with bright colorful patterns. They found time to lollygag, chat and wave out the window to sailors passing by.

Workers prepping the catch for canning. Water passed over the processing counters, rinsing salmon offal on to the floor and out to the sea.

Most fishermen and dockworkers were Scandinavian or Croatian (Thomas Hanson, former occupant of my home, fits the bill—his surname is a giveaway). They immigrated here with nautical skill sets and a determination to hack it in the land of opportunity.

I have to check myself here. It can be easy to over-romanticize what was sometimes grueling and dangerous work. One former Everett fisherman described fishing trips to Alaska as “months of boredom punctuated by sheer terror.”

Fishing wasn’t a guaranteed income. If the coho weren’t running or a competitor beat a fisherman to prime spot, tough luck. And possibly no paycheck.

For this reason fishermen could be quite competitive and protective of their favorite places to net salmon.

The self-proclaimed "Crab King" Jack Moskovita in his boat repair and salvage shop in Everett. He sold crabs out of a panel truck.

If I had an infinity of time I could scroll through a century's worth of newspaper microfiche at the public library, searching for the faces of Thomas and Alfretta Hanson, their obituaries.

There are more fragments of them out there, I’m sure: words or photos; pieces that could be cobbled into a biographical collage.

It’s this sense of history around us that makes living in Everett so valuable to me. I feel these stories personally, see them written on the streets and buildings once I know how and where to look.

This city is my story, too.

Fishermen circa 1940. Most fishing boats were hand-rowed until the mid-1930s. John Bakalich (left), a former WWII paratrooper, was known for his large arm muscles.

Today there is limited public waterfront access. Mostly it’s confined to a few isolated parks.

I believe what we need is a place for people to reconnect with the water: a broad, accessible, walkable, bikeable place to wade, frolic, sunbathe, beach comb and daydream. A place to buy ice cream off a cart on a boardwalk.

There are signs of this process beginning. There are new restaurants and housing going in on the waterfront. There’s the new footbridge that will connect Grand Avenue Park to the docks once more (the workers’ stairs for a new era).

It’s time to return to the sea.

It's who we are.

Special thanks to Dave Ramstad, local historian, educator, and advocate. His brain is an enthusiastic encyclopedia of all things Everett.

Richard Porter is a writer for Live in Everett. He lives here and drinks coffee.